Polish industry finds itself at the epicentre of a paradox. On the one hand, data shows an alarmingly low level of adoption of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and Big Data. On the other, it is these niche implementations that are triggering the most profound changes in the labour market, creating demand for new, elite competences. In the face of a demographic crisis and increasing competitive pressure from Europe, this divergence ceases to be a statistical curiosity and becomes a strategic challenge for the entire economy.

Two-speed transformation

Data for 2023 paints a picture of a two-speed digital Poland. Technologies perceived as mature and supporting day-to-day operations, such as cloud computing (used by 38% of industrial companies) and the Internet of Things (25%), have gained moderate popularity. However, they are often mainly used to optimise existing infrastructure, such as mail hosting or file storage.

The real divide is revealed in the area of technologies with strategic, transformative potential. Only 3% of industrial companies have implemented artificial intelligence and only 2% have used Big Data analytics. These figures become even more alarming in the European context. With an overall AI adoption rate of 5.9% in 2024, Polish companies rank penultimate in the European Union, ahead of only Romania. The EU average is 13.48%, with leaders such as Denmark at 27.58%. This is no longer just a lag – it is a fundamental problem of competitiveness.

Labour market: transformation instead of reduction

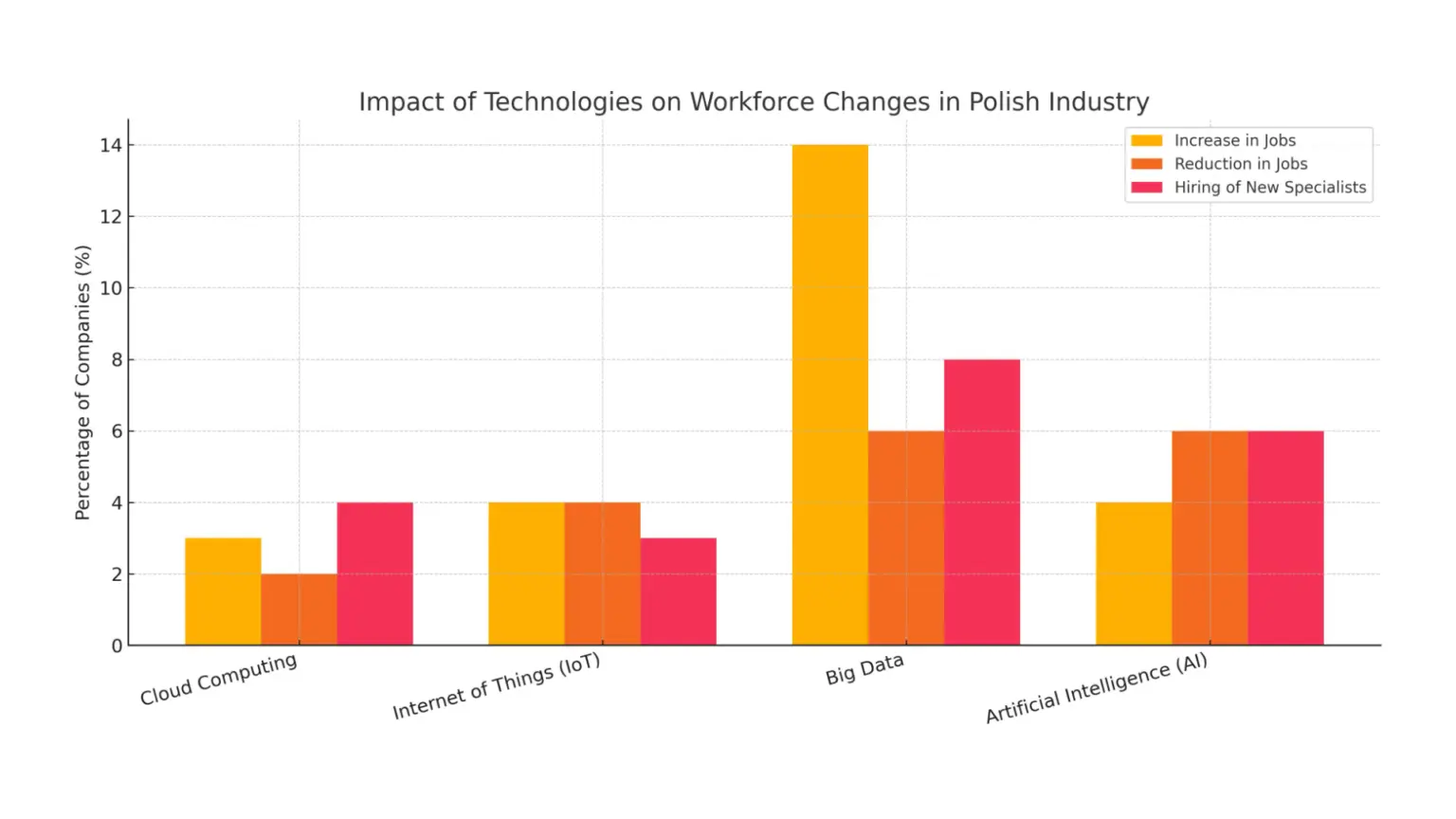

Contrary to widespread fears of mass redundancies, the data shows that the impact of technology on the labour market is much more complex. It is the most avant-garde technologies, AI and Big Data, that are acting as a double-edged sword, making deep restructuring rather than simple downsizing.

Companies that dared to implement Big Data reported the highest percentage of new job creation (14%), but at the same time a high percentage of reductions (6%). Likewise for AI – 6% job cuts and 4% job growth. This means that these technologies are not so much eliminating work as fundamentally recomposing it. They are automating routine and analytical tasks while creating demand for roles that require data interpretation, strategic thinking and management of new systems.

Crucially, the biggest beneficiaries of this change are highly skilled professionals. Big Data and AI implementations were the most likely to lead to the hiring of new experts (8% and 6% of companies respectively). A new professional elite is emerging in the market: data analysts (data scientists), software developers and AI and machine learning engineers.

This picture is further complicated by demographics. Projections by the Polish Economic Institute are clear: by 2035, 2.1 million people will have disappeared from the Polish labour market, including 400,000 from the industrial sector alone. In this reality, automation ceases to be a threat and becomes a strategic necessity for maintaining productivity and economic growth in a shrinking workforce. The real risk for the worker is not the replacement by a robot, but the collapse of his or her company due to a lack of competitiveness.

The glass ceiling of innovation: why are we standing still?

If the need for digitalisation is so pressing, why is its rate so low? The answer lies in a vicious circle formed by three mutually reinforcing barriers.

- Finance: for 67% of industrial companies, the main obstacle is the high cost of implementation. The problem is compounded by the difficulty of estimating return on investment (ROI), cited by 44% of companies.

- Competence: The second most frequently cited barrier is the lack of qualified staff, signalled by 52% of companies. The gap concerns both technical specialists and managers who understand the potential of technology.

- Strategy: as many as 44% of companies admit that digital transformation is simply not a priority for them. Nearly half of companies do not even know in which areas they could apply AI.

These barriers create an impasse: companies do not invest because they lack the staff to estimate profitability and implement solutions. The education market is not training specialists because there is a lack of mass demand. Breaking this cycle requires bold decisions at board level.

Strategies for the digital decade

Polish industry is facing the confluence of two powerful trends: global technological acceleration and a national demographic slowdown. The coming years will be decisive. Continued inaction risks a permanent loss of competitiveness, while bold and strategic action may open the way to a leap in development.

A synthesis of the analysis leads to one conclusion: Polish industry is at a critical point. It is caught between increasing pressure for innovation, dictated by global leaders , and decreasing availability of human capital. The persistent skills gap and strategic inertia at board level are the axis around which the future of the Polish economy will revolve. The window of opportunity to bridge this gap is closing – the next 5-7 years will determine whether Poland will join the ranks of digital innovators or fall behind.

By 2030, the labour market will be further polarised. Market forecasts clearly indicate a growing demand for specialists in fields that are crawling in Poland today. Roles related to AI and machine learning engineering, data analytics (Data Science), cyber security and cloud architecture will be key. At the same time, soft competencies that are complementary to technology will gain in importance: analytical and creative thinking, flexibility, mental toughness and readiness for continuous learning (lifelong learning). These are the ones that will enable effective management of technology-enabled teams and processes.

Polish industry is at a crossroads. Continued inactivity risks a permanent loss of competitiveness. To meet the challenges, business leaders must take decisive action:

- Invest in People, Not Just Technology: move from a mentality of ‘buying’ talent to ‘building’ it internally. Reskilling and upskilling programmes need to become a key part of business strategy, not just a task for the HR department.

- Strategy First: Digital transformation must be a boardroom priority, not an IT department experiment. Leaders must clearly communicate the business objectives behind investments and promote a data-driven culture.

- Build Foundations: Before companies throw themselves into the pursuit of AI, they need to ensure a solid foundation in the form of information governance (data governance) and a modern infrastructure. Many failed AI projects are due not to flaws in the technology, but to poor data quality.

The coming years will decide whether Poland will join the ranks of digital innovators or remain in the technological tail of Europe. The time to act is now.